The Kerner Commission’s 53 Year-Old Message for Minneapolis

Yes on 2 will expand our system of public safety

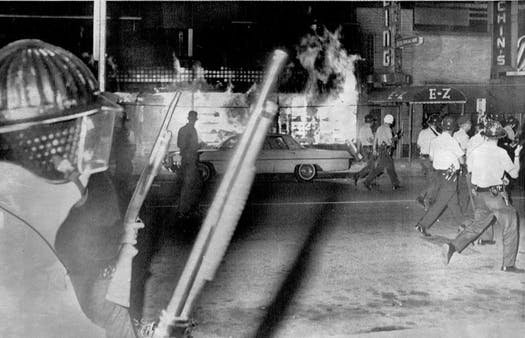

On July 21, 1967, Minneapolis police officers passed a blazing grocery store on Plymouth Avenue on the city’s North Side as they began to clear a crowd during a second night of violence. The officers marched shoulder to-shoulder down three blocks to clear a path for firefighters and to halt looting. Associated Press File Photo

This article was first published on Medium on October 28, 2021

In the wake of George Floyd’s killing by its tax-payer-funded police officers, there was overwhelming support to change the way Minneapolis does policing. Fast forward 18 months and Minneapolis voters are still struggling with how to address its system of public safety to make sure it doesn’t happen again. November’s ballot includes a charter amendment that would replace the Minneapolis Police Department with a “Department of Public Safety” that would “take a public health approach to public safety.”

While a large majority of residents can agree on the need for a different way, an unacceptable level of crime that mirrors that of other communities across the country have helped whittle the debate down to fear of “defunding” and “dismantling” the police.

But as American writer, author, educator, and The New Yorker contributor Jelani Cobb reminds us in his new book The Essential Kerner Commission Report, what Minneapolis is facing in the 2020s is not new.

The Kerner Commission (officially called the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders) was established by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967 after nearly two dozen destructive uprisings occurred in urban areas between 1964 and 1967. The most notable incidents of what Cobb calls “chaos of social retribution” included the Watts neighborhood in Los Angeles over the course of five days in August 1965, and back-to-back events in Newark, New Jersey and Detroit, Michigan in the summer of 1967. Minneapolis also experienced civil unrest in the summer of 1967 along North Minneapolis’ Plymouth Avenue over the course of two nights.

President Johnson specifically asked the commission to find the answers to three questions: “What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?”

As Cobb writes in the introduction to his book, most of the urban disturbances in the 1960s were triggered by police violence against Blacks. This includes the 1967 uprising on Minneapolis’s Plymouth Avenue. Yet, as the Kerner Commission found, American cities were not simply facing a crisis of policing. Rather, “Police are not merely the spark,” the report wrote, “They are part of the broader set of institutional relationships that enforce and re-create racial inequality.”

The Kerner Commission also provided extensive recommendations for how to, as Johnson put it “prevent it from happening again and again”: essentially, new community-based guidelines for how police should interact with the communities they serve, and invest in a whole new slate of community services around housing, employment, social safety net supports, and education.

As Cobb put it in an interview about his book, “What they said was that there needed to be other social service organizations, or outlets, that could address concerns that didn’t require someone with a gun to show up. And in a very succinct way, they were encapsulating the idea that has come to be known as ‘defund the police’ now.”

In 1968, the Kerner Commission report comes off as something of a warning, a warning that calls on Americans to fix what ails America. Unfortunately, in 1968 the society that received the report “had not the slightest appetite” for doing what needed to be done.

This all sounds eerily familiar to a Minneapolis that is still seeking ways to heal, not only from last summer’s police violence and subsequent destruction, but also from the longstanding systemic racial inequities that were laid bare last year to many white eyes. Now, with 20–20 hindsight, we in the 21st century can see how much we are paying the price for the inattention to the Kerner Commission’s warning.

But this year, Minneapolis has a chance to get it right.

In the days and weeks following George Floyd’s death, a campaign called “Yes for Minneapolis” coalesced around a new vision for public safety in the city. A coalition of 50 organizations helped collect 22,000 signatures from Minneapolis voters to put the public safety charter amendment on the city’s 2021 ballot.

The goal is to transform the provision of public safety in Minneapolis from a Police Department of armed and militarized licensed police officers to a Department of Public Safety, where police can coordinate with other service providers such as mental health professionals, unarmed community service officers, and others, depending on the situation. And yes, shift funding from police to other community-based resources.

Opponents of the measure are campaigning on the fear of defunding and dismantling the police if the measure gets passed. But Yes for Minneapolis recognizes what the Kerner Commission did 53 years ago: police violence against residents is often the spark that ignites a conflagration, made possible by systemic racial inequalities. Meeting people’s needs and addressing systemic racial inequalities will help create a more comprehensive version of public safety that will make our city safe for all communities.

This is our chance, Minneapolis. Let’s take the Kerner Commission’s 53 year-old lesson for addressing civil responses to police violence against Black communities. For if we turn our backs on this once-in-a-generation chance to do something different, we simply let the wound and the trauma fester until the next time an MPD officer kills an unarmed Black man.